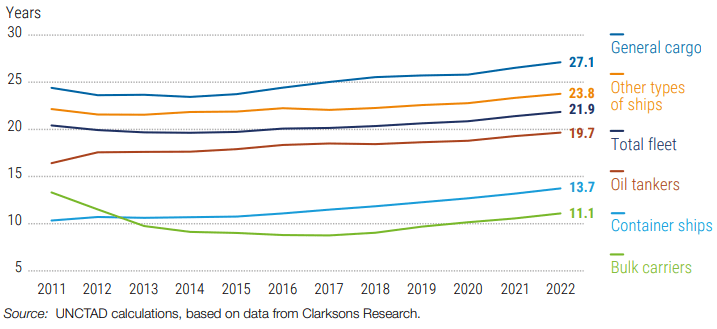

Since 2011, the world’s merchant fleet has been aging, according to a report by the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD).

By number of vessels, the current average age is 21.9 years, and by cargo capacity, 11.5 years.

Bulk carriers remain the youngest vessels, with an average age of 11.1 years, followed by container ships at 13.7 years and tankers at 19.7 years.

Average age of the commercial fleet, weighted by number of ships, by vessel type, 2011-2022

According to UNCTAD, the average age of ships has been increasing partly because, in the wet and dry bulk sector especially, shipowners have been uncertain about future technological developments and the most cost-effective fuels, as well as changes in regulations and carbon pricing.

Therefore, in order to benefit from today’s high charter and charter rates, they have kept their older vessels in operation.

In 2020, in gross tonnage terms, ship deliveries contracted, but in 2021 they increased 5.2 percent.

However, shipbuilding volumes remain below 2014-2017 levels.

Commercial fleet

Far East and North America routes, between the first quarter of 2020 and the last quarter of 2021, delays increased from two days to 12.

Meanwhile, between 2020 and 2021, the median turnaround time for containerships increased 13.7 percent.

To some extent, the ton-mile trade is being sustained by market and supplier substitution.

The Russian Federation, faced with economic measures and other restrictions, is seeking alternative markets, while European importers are considering other sources of supply.

Ton-mile demand is also likely to be boosted by African countries sourcing grain from further afield.

Regions

Since the onset of the logistics disruptions at the end of 2020, there has been a global decline in liner shipping connectivity, albeit with variations between countries.

The world’s most connected country remained China, which extended its lead.

And India expanded its regional connections by improving port capacity.

Similarly, in North Africa, the continued development of port infrastructure helped mitigate the impact of the pandemic.

These gains were offset by declining connectivity elsewhere, including major economies.

In the United States of America, for example, the operational performance of container ports was undermined by weak West Coast port infrastructure as a result of long-term underinvestment.

But the picture was even worse in parts of the developing world: during this period, most of Africa and Latin America and the Caribbean suffered significant reductions in direct connections.

![]()